Small flocks have always been at the forefront of grassroots local production. During the COVID-19 pandemic, small producers proved that they’re an important part of continuity and resilience.

The coronavirus shelter-in-place exposed issues of how American food production works – or doesn’t. Local sources became more important for putting food on the table. Community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs, farmers markets, growing your own produce, and appreciating your local farmers became the 21st-century version of victory gardens.

When the COVID-19 shutdown disrupted commercial food supplies, small-flock keepers stepped into the breach. I found myself connecting backyard and small-flock keepers with my circle of friends, picking up and delivering eggs. Backyard-flock keepers had eggs, even when the grocery store didn’t. Their coworkers and neighbors enjoyed the bounty, too. Sharing eggs is a popular way to educate friends, neighbors, and coworkers on the benefits of raising chickens, while supporting farmers and small producers!

“Everybody can be a part of making this change that’s going to be better for future generations,” said Shelley Oswald of Old Time Farm in Pennsylvania. She and her husband sell heritage breed Milking Devon beef, Partridge Chantecler chickens, Standard Bronze turkeys, and related products. “The consumer has the power to make the change.”

Shelley Oswald, Old Time Farm

Food Supply Chains

The coronavirus crisis stretched the commercial food distribution system. Shelves in grocery stores emptied out. Distributors were unable to meet consumer demand. As supplies arrived, stores adapted by limiting purchases to share the short supply with as many customers as possible.

In December 2019, Ruchir Sharma, chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, wrote in an essay in the New York Times, “Small is the New Big Thing:”

“Quietly, global economic forces are shifting in ways that could set the stage for a comeback by smaller nations and businesses in the 2020s. … Internet platforms allow small companies to bypass stores, win public trust instantly through consumer reviews, and build a brand on cheap internet ads, even free YouTube videos. … The fastest-growing American food and beverage manufacturers are small ones. … If the 2010s were a golden age for the world’s largest economy and its megacorporations, the 2020s are likely to be remembered as the decade when smaller was beautiful again.”

Supply Chains Hiccupped

The COVID-19 shutdown revealed the pitfalls of the national supply chains. Consumers bought out supermarket supplies, and egg shortages showed up right away. Although industrial egg producers who supply eggs to restaurants and institutions lost those high-volume customers, they were unable to step in to supply grocery stores because they didn’t have the cartons and equipment for individual consumers. They were faced with destroying their eggs, or even whole flocks, for lack of a way to sell them.

Shelley Oswald, Old Time Farm

In one case, a small-flock egg producer, Timi Bauscher of The Nesting Box Market and Creamery in Kempton, Pennsylvania, who has 1,700 hens and sells 80 to 100 dozen eggs a day, partnered with a commercial producer to sell eggs. She heard about Josh Zimmerman’s operation – 80,000 hens laying 60,000 eggs daily – which he sold entirely as liquefied eggs to cruise ships, hospitals, and school cafeterias. With those places not fully operating, he had no outlet for his flock’s eggs. And, without a market for eggs, he’d have to euthanize his flock.

Bauscher connected with him, and then she used her social media connections to advertise the eggs. Hundreds of buyers wanted them, so she arranged to relocate from her farm stand to a local community center, with the help of volunteers.

This story illustrates how smaller operations can quickly adapt to changing market conditions. Industrial operations are stuck; they can only conduct their operations one way. If that’s blocked, they come to a full stop.

“We’re [smaller operations] like Lucy and Ethel on the candy line,” Oswald said.

The distribution outlets, the grocery stores where the end-user buys them, are far away from the egg production farms that are the result of farm consolidation. Giant producers controlling the source of production in a few hubs make sense to corporate executives focused on the financial bottom line, but concentrating production is a liability in a crisis.

American national policy encouraged farm operations to consolidate in the past few decades. Earl Butz, secretary of agriculture under Presidents Nixon and Ford, told farmers, “Get big or get out.” Agribusiness conglomerates bought out small operations and consolidated into giant corporations.

The focus was on the profits to be squeezed out of economies of scale. Bigger means lower cost per unit. But the efficiency of concentrated commercial operations makes those enterprises less resilient. It’s like the old image of how long it takes to turn an aircraft carrier; smaller producers can be more flexible and nimbler than larger ones. The logistics of changing crops, harvesting, and preparing food for sale are more complicated and difficult for big, concentrated operations than for smaller producers.

Big corporations, with chicken houses of hundreds of thousands of chickens, all identical so that they can be processed on an assembly line in a single central processing plant, means that any glitch in the system immediately affects a lot of chickens and a lot of workers.

“There will always be a tradeoff between efficiency and resilience (not to mention ethics),” author Michael Pollan wrote in the New York Review of Books. “The food industry opted for the former, and we are now paying the price.”

Local Food

Photo by Talley Farms Fresh Harvest

Enter small, local operations. They’ve always been here, even as the regulations governing agriculture have been aimed nearly exclusively at helping corporate agribusiness. Consumer preferences have been changing; they’re willing to pay higher prices for fresh produce from farmers markets and farm-to-plate restaurants whose chefs feature local produce. That increased demand makes it possible for small producers to succeed financially.

That’s the rub: Local food from small producers costs more. A driving force of getting big was to produce the cheapest food possible. In that, big corporations succeeded. Americans now spend only about 10 percent of their income on food, down from 16 percent in 1960. But consumers started noticing that the cheap supermarket tomato was tasteless compared to the vibrant flavor of the ones fresh from local growers. They’re willing to pay more.

Food markets changed as supermarkets added local produce to their departments. Whole Foods and other grocery chains made quality their market niche, and then Amazon bought Whole Foods and started delivering groceries.

Photo by Frank Reese, Good Shepherd Poultry Ranch

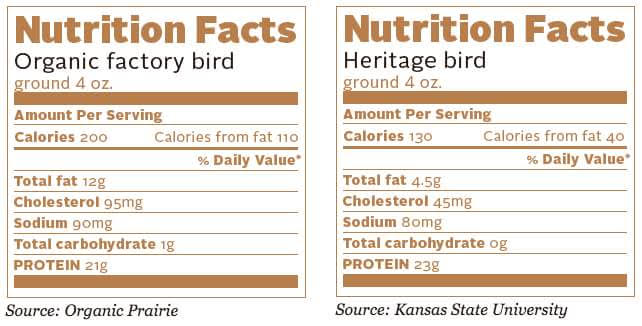

Nutrition also plays a role in consumers’ preferences for local foods. Frank Reese of Good Shepherd Poultry Ranch in Kansas is raising chickens according to the American Poultry Association’s Standard of Perfection. Commercial chickens are an industrial hybrid, their genetics developed and owned by agribusiness companies. The industrial birds reach their market weight at about seven weeks and then are processed for meat. Reese’s grow for several months to reach market weight. A Kansas State University nutritional comparison found that his GSTR Heritage Chicken ™ is significantly different nutritionally from commercial hybrid free-range organic chicken:

New Hampshire has 21 percent more protein and 21 percent less fat per serving.

Jersey Giant has 23 percent more protein and 37 percent less fat per serving.

Barred Plymouth Rock has 26 percent more protein and 37 percent less fat per serving.

Cornish Indian Game has 26 percent more protein and 47 percent less fat per serving.

Heritage chicken has three times the Omega 3 oils than commercial chicken.

Local Supply Chains

Farmers markets have expanded in recent years. They give local producers a way to reach customers, and their local control made it possible for them to adapt to safe practices during the pandemic. Social distancing, masks, and business continue on. Awareness of the significance of nutrition and taste, the culinary movements, and other factors, have made local producers more important, and these local producers have made the case for paying farmers fairly.

Photo by Talley Farms Fresh Harvest

Buying from a local producer such as Old Time Farm keeps the money in the community. Buying from corporate retailers sends money to headquarters and shareholders. Small producers are members of their community, doing business with other locals.

CSAs saw a big increase during the shutdown. To participate in a CSA, customers sign up with a CSA farm as members and get a box of produce every week or two. Boxes may be picked up from the farm, a central location, or delivered to the member. Sometimes, members pay in advance, giving the farmer cash to operate their farm, or they may pay weekly, giving the farmer a reliable income.

Talley Farms Fresh Harvest in California saw CSA orders jump from about 2,000 boxes a week to between 5,000 and 6,000. While they don’t expect to keep all those customers, many will probably continue after the crisis is over.

“I’m encouraged that people are finding the joy in eating and cooking at home, spending time with family,” said Andrea S. Chavez, manager of the Talley Farms Box Program. “I think we will see a lot of changes.”

Backyard Flocks

The time is right for people who have been on the fence about starting a backyard flock. At our local feed store, we lined up and took a number to buy a few chicks. Feed stores sold out.

Backyard chickens became a thing in the early 21st century. Little did anyone suspect that raising chickens in small flocks could be a harbinger of changes to food systems.

Small flocks focus attention on humane treatment of domestic livestock. As backyard keepers learn about their chickens, their hearts are softened to the suffering of chickens that live in cages so small they can’t flap their wings, chickens that never see the sun or scratch in dirt. Keeping a backyard flock makes it hard to ignore the gritty realities of concentrated animal feed operations.

Photo by Shelley Oswald, Old Time Farm

The requirements of large production facilities relegate concerns about animal welfare to the profit and loss sheet. The suffering of animals doesn’t fit into those considerations. Small-flock owners who watch over their birds can allow themselves more latitude in caring for them, beyond the basics of health and disease and into the quality of life.

Small flocks are an excellent teaching tool. The Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago uses hatching chicks as part of its genetics exhibit. The exhibit hatches Java eggs for Garfield Farm Museum in LaFox, Illinois, which helps them improve their Java flock. The museum has been able to hatch far more eggs than Garfield Farm could have hatched on its own.

Classroom chickens introduce children to chickens and help them understand that food has to be grown and raised. It doesn’t magically appear at the grocery store.

As backyard chickens have become more popular, communities have eased restrictions to allow them. Austin, Texas, even offers a $75 rebate to support backyard flocks. It’s part of the composting element of their solid-waste reduction program.

Better food, from local people, gives small-flock owners a marketing advantage. The experiences consumers had during the COVID-19 crisis may influence permanent changes in American food systems after the pandemic is over.

Small flock keepers will save the world! We’ve long been out in front of the pack.

1 Comment

During the COVID pandemic I was asked by two local mom and pop local grocery stores to provide eggs when they were unable to get eggs I also had people drive many miles to buy eggs when they could not find any for their family and friends. I also sold eggs to two local restaurants.

I was glad I could help and helped me as well.

Frank Reese