Poultry parasites can cause harm to individual birds, or the whole flock. Elizabeth Mack identifies some common parasites to watch for and what to do about them.

For small flock chicken owners, nothing raises more alarm than finding out that one of your chickens has parasites. Chickens can pick up internal parasites from ingesting contaminated feed, water, or bird droppings, or from intermediate hosts like earthworms or snails that carry contaminated eggs. Wild birds are the main culprit of external parasites, but chickens can easily spread lice and mites to each other in the nesting boxes, on the roost, or even during a molt when feathers are shed. Taking precautions, including following the principles of a good biosecurity program, can go a long way in preventing a severe infestation.

Identifying Parasites

External

The most common external parasites on poultry are lice and mites. Lice, small, wingless insects, move quickly, and though tiny, can be seen moving on a chicken’s skin or feathers. While several species of lice can infest poultry, the most common is the body louse (Menacanthus stramineus).

Menacanthus stramineus nymphs on chicken feather. Getty images.

There are two suborders of lice, which are characterized by what they eat: The Mallophaga, or chewing lice, feed on skin cells and debris from feathers, and the Anoplura, or sucking lice, that feed on mammal blood. Once off the bird, lice will die in a few days. But while they’re on the bird, they can deposit numerous eggs, or nits, which will hatch within a week. Excessive preening is a telltale sign of a lice infestation in chickens. The stress from a bad lice infestation could cause birds to eat less, leading to weight loss, decreased egg production, and feather and skin damage in severe cases.

Severe lice infestation around the neck of bird. Photo courtesy of Dr. F. D. Clark, University of Arkansas

The other nasty external parasite, mites, are much harder to see than lice. These mites congregate around the bird’s vent and tail, feeding on its blood. Like lice, mites can cause decreased feed intake, weight loss, and a drop in egg production. The most common mite in U.S. poultry is the Northern fowl mite (Ornithonyssus sylviarum), but the chicken mite, or red mite (Dermanyssus gallinae), is also found in North America.

Northern fowl mite infestation. Photo courtesy of Dr. Jean Sander

In a heavy infestation, feathers can appear discolored, and in severe cases, effects of mites can lead to anemia and even death. Scaly leg mites (Knemidocoptes mutans), while usually not a death warrant, can lead to lameness or deformed toes if not caught early.

Internal Parasites

While external parasites, such as lice and mites, are mostly a nuisance, internal parasites can be much more dangerous to a backyard flock. Small infestations in adult birds might go unnoticed and can be left untreated, but a severe infestation can lead to death, especially in young chickens.

Poultry are at risk from several types of intestinal worms, including large roundworms, cecal worms, threadworms, and several different species of tapeworms. A chicken with internal parasites can suffer from decreased feed absorption, leading to weight loss, or, in young birds, the inability to gain weight. Internal parasites can also prevent the absorption of nutrients, leading to deficiencies and lowering of a bird’s immunity to diseases.

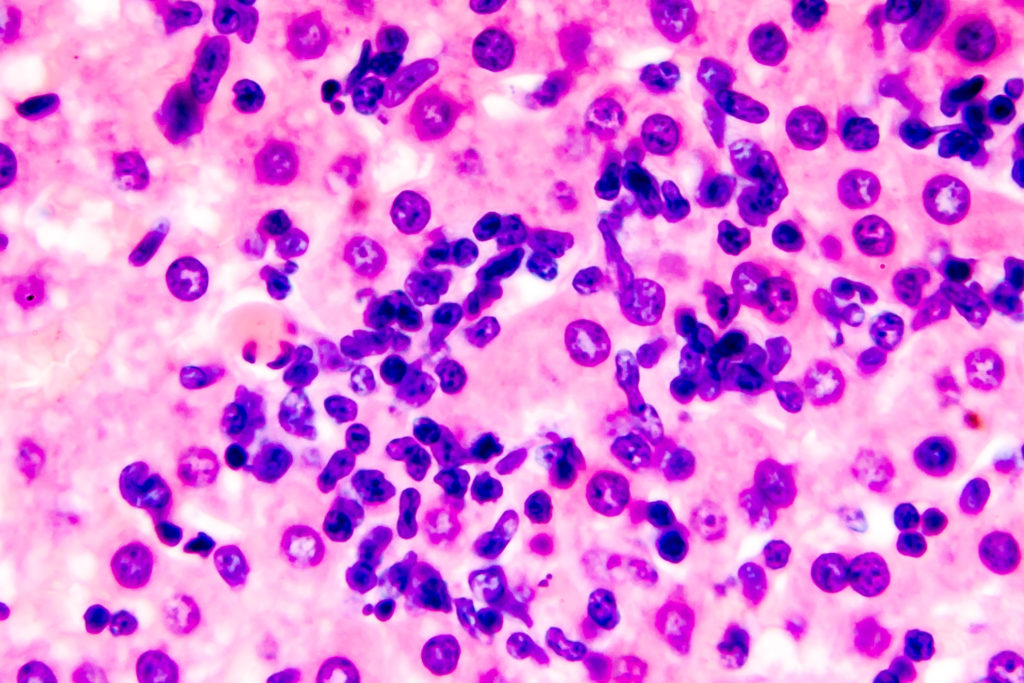

Coccidiosis, coccidia in liver with light micrograph.

Coccidia, a protozoan, is a common internal parasite. While adult birds develop immunity to the parasite, young birds who haven’t built up their immunity can suffer a serious illness. These particular parasites multiply in the intestinal cells, causing cell damage, hemorrhages, dehydration, and, in sever infestations, even death.

First Line of Defense

While internal parasites are impossible to see in all but extreme cases, the detection of external parasites is often a good indication that internal parasites exist. If the infected bird is new to your flock, it might not have previously been in the best conditions. If your flock is free-range, the risk of exposure to pathogens from wild birds is greater, leaving your flock susceptible to outside pathogens.

According to Dr. F. D. Clark, Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, Extension Poultry Health Veterinarian and Associate Center Director for Poultry Extension in the Center of Excellence for Poultry Science with the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture, free-ranging your birds is okay, but there’s always a risk: “You lose security. Birds exposed to the outside environment are more at risk. It’s a matter of degrees of security.” Dr. Clark recommends diligently checking your flock for both external and internal parasites if free-ranging.

Wild birds find their way inside of fenced run. Photo by author.

Dr. Clark also recommends having your vet do a routine parasite test, called a fecal flotation, twice a year; once in the spring, and once in the fall. If it comes back positive, your practitioner will prescribe the appropriate treatment plan for the specific pathogen. If a local avian vet isn’t available, state extension offices often have labs that can run the test.

A one-size-fits-all treatment, however, isn’t effective. “I don’t recommend doing routine deworming,” adds Clark. “You want to know what worm is in there. See what parasite you have, then tailor your treatment plan.” For example, most of the dewormers available don’t have much effect against tapeworm. Prevention starts with building a relationship with a local vet who knows chickens. “Work with your practitioner. Follow their recommendations on prevention and examinations,” says Clark.

Prevention Starts with Biosecurity

Chicken owners can take specific precautionary measures to ensure they’re not only getting a healthy chicken, but are raising their flock in the best environment to prevent parasites and disease. First, make sure to get your birds from a reputable source. Ask if they’ve been vaccinated. If you’re getting your chickens at a local hardware or feed store, where did they come from? How are they being cared for? Do they look healthy? Are they energetic and alert?

Once you bring new birds home, Dr. Clark recommends keeping chickens isolated from the rest of the flock for a minimum of 30 days. “Longer is even better, as most diseases will break and emerge in about three weeks or so,” says Clark.

Clark recommends doing a physical check weekly, if not daily, for parasites. If your flock seems restless at night, try hanging up a white handkerchief. Red mites will be visible in the morning. Scaly leg mites will be visible on the leg and look like dried bread crust. The Northern fowl mite will appear as tiny dark red or black specks on the bird’s vent and tail. While these mites tend to be more prevalent in the fall and winter months, they can be found anytime, so keeping a watchful eye is critical for good biosecurity.

Other biosecurity measures include keeping visitors out of your coop and run, especially if they have their own flock. Also avoid sharing tools or cages with other flock-owner friends, as pathogens can live and hitch a ride on either. Keep a dedicated pair of shoes only for chicken use to avoid contamination. Get quality, age-appropriate feed, and avoid spoiling your flock with goodies from your kitchen. If kitchen scraps are moldy or spoiled, they’re not good for your flock either. Keeping out wild birds and other vermin from the pen is essential, and try to keep your flock away from wild birds in general, though that’s often hard to do.

While most backyard chicken keepers have a soft spot for rescues, it’s not a good idea to bring a troubled hen or rooster into your flock, as it could be hiding an infestation or disease. Always follow a minimum 30-day quarantine for all new birds, and avoid adding an “extension” onto the existing run. House newbies in a coop and pen as far away from your flock as possible.

Special Considerations

Poultry judging at the county fair, with chickens in close proximity. Photo by author.

Following good biosecurity measures is essential for backyard poultry keepers, but if you plan on showing your birds in the county or state fair, you’ll need to be even more vigilant. Your vet might recommend to deworm four times a year. Moving birds to different locations in a cage that’s right next to another could lead to the spread of dangerous pathogens. Dr. Clark assisted with a study looking at fecal samples from birds in exhibitions. The results showed that a large number were positive for small amounts of internal parasites, such as round worms, cecal worms, and coccidia. “Those birds looked like the picture of health,” recalls Clark, “so you wouldn’t know it by looking at them.”

Caged poultry exhibits at county and state fairs are often displayed for 5 to 10 days. Photo by author.

Alternative Treatments

While the use of apple cider vinegar and diatomaceous earth have been thought to prevent parasites in chickens, Dr. Clark says there hasn’t been any scientific evidence to back up those claims — or negate them. “Some individuals swear by diatomaceous earth; others say it doesn’t work. The verdict is still out,” Clark says. Clark adds that new research, however, has shown that botanical oils, specifically cinnamon, oregano, lemon, rosemary, garlic, and thyme oil, used individually or in combinations, have shown promise. Juniper oil was shown in one study to be effective against red mites. Oregano oil has been tested as a treatment for coccidia and histomoniasis or blackhead disease, with promising results. While more data is needed, Clark says, these alternative preventative treatment methods show potential.

While the availability of over-the-counter antibiotics and deworming products were once the norm, now many are only available as prescriptions, since antibiotic resistance in poultry is a growing concern. With fewer treatment options, it’s even more important to follow regular preventive measures. Dedicate an adequate dust bathing area for your flock, keep their coop and run clean and free from wild birds, and be diligent with a quick daily—and more thorough weekly—inspection. Build a relationship with a vet who understands chickens, so if the need arises, you’ll have an expert on your side. Eliminating risk and following a few preventive steps is the best medicine for a thriving, healthy flock.

Sources:

“Management of External and Internal Parasites of Outdoor Poultry Flocks.” F. D. Clark, DVM, PhD, DACPV. Extension Poultry Health Veterinarian – University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture.

Freelance writer Elizabeth Mack keeps a small flock of chickens on a 2-plus acre hobby farm outside of Omaha, Nebraska. Her work has appeared in Capper’s Farmer, Out Here, First for Women, Nebraskaland, and numerous other print and online publications. Her first book, Healing Springs & Other Stories, includes her introduction—and subsequent love affair—with chicken keeping. Visit her website BigMackWriting.

4 Comments

It is a shame that we are now left with NO OPTIONS for worming our chickens. Individual homeowner flocks pose no danger to antibiotic resistance. Pigs, cows and other animals sold for the market are the real threats, but you will not see their options taken because they have money for lobbyist to buy of our representatives.

Anyone know of a website in Austraila that will ship to the US? They have an excellent chicken feed with parasite meds mixed in, which is the best way to keep your flock parasite free. This method is now becoming popular with horses as a way to keep them parasite free, which seems to be much more effective than waiting until they get super worm infections that are becoming harder to treat.

This might be a good place to start for information on Australian chicken sites for backyard owners: http://www.backyardpoultry.com/

I also want to be clear about the content of this article. There are lots of options mentioned in the article about ways to approach deworming your chickens. Dr. Clark is recommending that “routine” deworming may not be the best way to go in the long run.

Love your information but can’t pin it or print it. No way to save it. Help!

Hi Leah,

I’m forwarding this to our IT department. You *should* be able to pin, so I’m not sure what’s going on. Thanks for reaching out and glad you like the information!